EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which went into force in 2021, explicitly states that the purpose of Green Investment Funds is to deliver impact to support the EU’s Green Deal. But are these funds delivering an impact that aligns with environmental or societal objectives? That is a tricky question to answer. Instead of focusing on reported ESG metrics, which is problematic for several reasons, the researchers decided to look closer at the actual holdings of the green funds. Why? If green funds are supposed to shift capital to more sustainable companies, they should be distinguishable from conventional funds in terms of the assets they hold.

They examined the portfolio allocations made by 6888 equity funds traded on European markets and the 24549 assets they hold on one specific day, 22 May 2023. The funds were classified into three groups based on the SFRD taxonomy. (The regulation provides the industry with a common language on what qualifies as a green investment. It is also a part of an effort to keep greenwashing in check and increase investment flows towards more sustainable activities.)

- Dark-green (aligned with SFRDs article 9; the transparency of sustainable investments funds claim to have sustainable investments as their primary objective).

- Light-green (aligned with article 8; the transparency of the promotion of environmental or social characteristics funds claim to promote environmental and social impact).

- Conventional funds (aligned with article 6; the transparency of the integration of sustainability risks. These funds do not claim to have a sustainability scope but must disclose how they have integrated sustainability-related risks into their investment decisions).

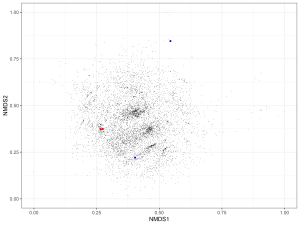

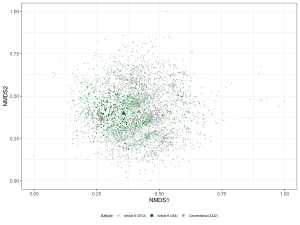

To compare and visualize the three fund groups, they used a computational method initially developed by numerical ecologists called non-metric multidimensional scaling. In short, this method takes all the funds and their respective holdings as input and produces an output of all the funds plotted in a two-dimensional space according to the similarity of each fund’s holdings.

Given the SFRD objectives with Green Investment Funds, the researchers expected the output to reveal systematic differences in how the Dark-green, Light-green, and Conventional funds are allocated. But that is not what happened. When plotting the complete set of funds classified as Dark-green, Light-green, and Conventional funds, they found little evidence to suggest that green funds invest in assets that conventional funds do not invest in.

In the next step they compared Green investment fund and Conventional fund holdings within fund categories:

- Global Equity Large Cap Funds

- Europe Equity Large Cap Funds

- Europe Equity Midsmall Cap

- Energy Sector Equity

Overall, the findings of the within-Fund Category comparison mirrored the patterns observed for Green investment funds in relation to Conventional funds in the full Universe of funds. One exception is the Energy Sector Fund Category where the separation of the Green investment funds’ and the Conventional Fund’s clusters is very distinct.

In the concluding remarks, the researchers write:

“Taken together, our results suggest that by and large, the EU’s SFDR regulation has done little to shift the actual allocation of capital to support a distinct set of (presumably green/sustainable) companies, as was the objective of the Green Deal. This suggests that green investment funds with non-distinct portfolio allocations will need to differentiate themselves by engaging with the corporations in their portfolios. Green investment fund managers can thereby claim to deliver impact despite their portfolio allocations, but will need to demonstrate that their engagement activities are in fact delivering year on year progress against publicly set environmental and social targets for such claims to be credible.”